Dr Alex Broadhead is a Teacher in the University of Liverpool’s Department of English

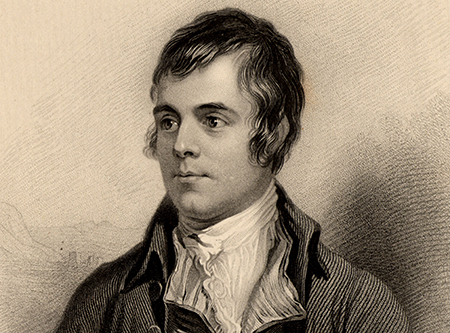

“This Saturday, people all over the world will congregate to feast upon a spicy sheep’s stomach, but not before they’ve recited a poem in its honour. The occasion is Burns Night, the poem is Robert Burns’s To a Haggis, and this weekend’s festivities may come, in the decades ahead, to take on a unique historical significance.

“The year 2014 is, of course, the year of the Referendum for Scottish Independence. Since the nineteenth century, Burns Night has, unofficially, served as national Scotland day.

“But, if Scotland does vote yes this summer, what I will be interested to discover, as a Burns scholar who has lived his entire life in England, is whether people south of the Tweed will develop a new curiosity about Burns’ poetry. It’s a strange paradox that Burns Nights continue to grow in popularity in England and yet the works of the poet himself remain neglected on English school syllabuses and University reading lists.

“The owners of the restaurant down the road from where I live in Sheffield were so excited about Burns Night that they had it fifteen days early. Even so, this enthusiasm doesn’t seem to translate into a desire to read the poet: Burns is rarely spotted on shelves of the local high street bookshops (or what is left of them).

“The reasons for Burns’s under-representation in English educational institutions have been rehearsed elsewhere. And, needless to say, I find the arguments for why English people should read Burns’s poetry much more compelling than the explanation for why English people don’t read his work.

“So here is a list of Three Reasons Why a Robert Burns is for Life, Not Just for Burns Night:

1) Burns will change the way you think about language. He’s famous for writing in the Scots language, but Scots was just one of the many languages and dialects at his disposal.

“His poems leap from formal to informal English and from the regional dialect of his native Ayrshire to the artificial, literary language of his Scots predecessors. Burns’s uniqueness doesn’t lie in the fact of his multilingualism, however. Rather, it lies the way he uses different varieties to confound your expectations of what is linguistically normal. Have a look at the first few lines of his epistle to To William Simson, Ochiltree (Simson had sent Burns an excessively flattering letter; Burns suspected a prank, and this was the first stanza of his reply):

I gat your letter, winsome Willie; (gat = got)

Wi’ gratefu’ heart I thank you brawlie; (brawlie = very much)

Tho’ I maun say’t, I wad be silly, (maun = must; wad = would)

An’ unco vain, (unco = very)

Should I believe, my coaxin billie, (coaxin billie = wheedling fellow)

Your flatterin strain.

“It’s hard to keep up with this sentence, such are the minute and labyrinthine movements it makes between Scots and English.

“What starts off as the recognisable English expression I thank you, for instance, flips to Scots at the last moment with the addition of brawlie. Burns switches between languages for all kinds of reasons. Here, I think, it’s bound up with the curious way in which he alternates between brutal frankness and elaborate politeness.

“These kinds of inconsistencies invite Simson to doubt Burns’s sincerity: to wonder if the pranker has now become the prankee. Burns’s slippery approach to language keeps Simson – and us – guessing.

2) Romanticism wouldn’t have happened if not for Burns. Nigel Leask, the author of a 2010 study of Burns, has argued that the poet’s work (and that of his editors) “profoundly shaped the development of British and Irish Romanticism”.

“Burns’s influence is present when Wordsworth celebrates the language of low and rustic life. It is there when Keats claims that “beauty is truth, truth beauty” (it was at the grave of Burns in Dumfries that Keats realised the job of the poet was to capture ‘the real of beauty,’ as a sonnet he wrote on location makes clear). And it is there in Byron’s poetry, in its strange mix of earnestness and irony, and its complex tonal modulations.

3) Burns got there before the Magic Realists. Thomas Carlyle said of Burns that “the Song he sings is not of fantasticalities; it is of a thing felt, really there.” This has always struck me as a strange thing to say about a poet whose works feature talking sheep.

“Yet the image of Burns as a writer who simply recorded what he saw around him was an especially pervasive one in the Victorian period. There is perhaps a grain of truth in what Carlyle says, insofar as Burns’s poems – even the ones featuring speechifying ewes – offer an incredibly vivid picture of the practices, customs and material objects of the Ayrshire countryside.

“Just as he does with different languages, Burns transforms both reality and stock supernatural tales by combining them in strange, unsettling and audacious ways. Perhaps the best example of this is Death and Doctor Hornbrook,’ in which Burns nearly gets into a drunken knife fight with the grim reaper, before sitting down with him for a friendly chinwag.

“Bookmakers may currently be offering unfavourable odds for a Yes vote. I haven’t yet worked up the courage to enquire whether they would accept a bet on more people reading Burns’s poetry. But, next year, as you tuck into a spicy sheep’s stomach, put your ear close to it.

“For if the spicy sheep’s stomach could talk it would tell you: A Robert Burns is for Life, Not Just for Burns Night.

The Language of Robert Burns: Style, Ideology and Identity by Dr Alex Broadhead is published this month by Bucknell University Press.

Many congratulations to Alex on his book, and thanks for this Viewpoint.

People might be interested to know that there is a (posthumous) link between Burns and Liverpool, dating from the very end of the eighteenth century, and the subject of a short blog in the University Library’s Special Collections and Archives series Manuscripts and More:

http://manuscriptsandmore.liv.ac.uk/